Focus, Windows and UNIX

Focus is another one of those things that works differently between autistic people and neurotypical folks. Here’s an analogy I’ve been playing with a bit…

I kind of see it like the difference between a graphical operating system like Windows or macOS and a command prompt based one like UNIX or DOS.

Neurotypical people are a bit like Microsoft Windows. Or maybe the comparison should be the other way round; I suspect Windows was invented to be more like neurotypical people. (And yes, I know it copied other operating systems.) I suspect the autistic people were fine with UNIX or DOS.

Windows looks pretty friendly. It has lots of things on the go at once. It will usually have a dozen or so things running in the tray at the bottom right, including the clock and the printer driver. There might well be news feeds, messaging apps and weather forecasts there too. You can have quite a few windows open at once too, though only one active window at once, and the user often keeps that window maximised so it gets most of their attention.

If you actually dig into what is going on with Windows though, it can only really do one thing at once, but it keeps switching between jobs so that on a good day the experience is pretty seamless.

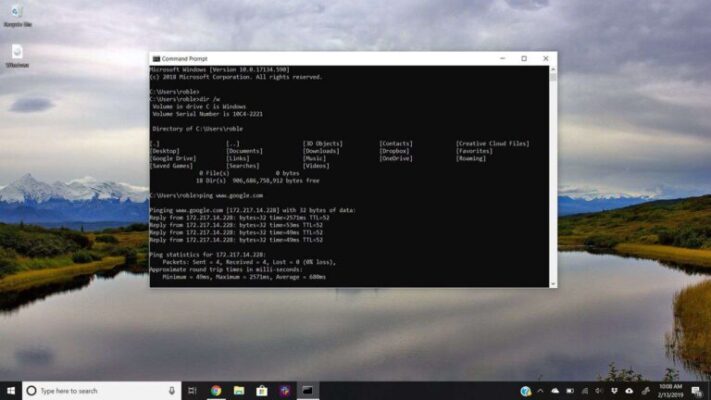

UNIX can do a lot of the same things, but looks very different. It doesn’t have a graphical user interface. The main way of interacting with it is typing commands in, which need to be phrased exactly right, otherwise nothing happens (or totally the wrong thing happens). It isn’t obvious how to get things done, but once you manage it, you can do almost everything Windows can do, and a good few things Windows can’t do.

But this is about focus. As I understand it, UNIX does one thing at once, and does it with all the resources it has available. Once you give it a command, it won’t let you do anything else until either it’s finished or you tell it to stop. If you interrupt a task, you have to restart it from the beginning. There is no pause, no window switching, no multitasking. On UNIX, you can’t even check the time in the middle of doing something else.

The positive side of this is that for some complex tasks it’s much faster than Windows. Even now, I sometimes use command line graphics and video editors because if you want to resize every one of 200 images to 320×240, crop if necessary and then put them in a grid pattern, or if you want to take a section out of a video file and save it as a separate file, it can do it with a couple of commands in a few minutes. Why is it so much quicker than Windows? Because it doesn’t bother doing everything else at the same time. It doesn’t keep on updating the screen. It doesn’t bother showing you the graphics it’s editing. It doesn’t let you check your e-mail at the same time. It might give you some text every now and then to show you it’s not crashed, but that’s it.

And that’s how I see the difference in focus between me as an autistic person and neurotypical people. Neurotypical folks mostly pay attention to one thing at once – the active window – but they have loads of other stuff going on in the background. They are aware of what the time is, what they’re doing later in the day, they have messages or conversations pop up and then pop down again and so on.

Me? Not so much. If I’m in the middle of a task, I’m not going to be able to tell someone what the time is or reply to a message and then just get back to it as if nothing had happened.

I sometimes say that phoning me when I’m in the middle of something else is like sneaking up behind me then slapping me with a wet fish until I pay attention. I can’t just switch windows then switch back again afterwards.

And it’s not always easy for me to understand what I need to do. Back in the days when I followed instructions, they needed to be precise and accurate, just like text commands for UNIX. And if they were slightly wrong or unclear, I’d usually get the wrong end of the stick, then get angry with the questioner when I didn’t get full marks.

But the plus side of this is that once I’ve managed to focus on something, I can focus really well, dig conceptually deeper than most people, make connections that lots of folk would miss and produce huge amounts of work in a couple of hours. That’s not the whole story of why I’m so good at exams, but it’s part of the story. Exam conditions are pretty much ideal working conditions for me.

It’s entirely possible for me to vanish into work, computer programming, website design or gaming for several days at a time. Sometimes I remember to eat!

The common term for that is “autistic hyperfocus”. I can’t always choose what to hyperfocus on – it needs to be something requiring enough brain activity. I can’t hyperfocus on a game of Snakes and Ladders for example.

Another factor that drops out of this analogy is what’s called “executive function” – essentially the whole area of being organised, prioritising, etc. Essentially, that needs someone to be able to split-screen and work with two windows open at once, which means that autistic people often really struggle with it, which is known as “executive dysfunction”.

People don’t usually accuse me of that though, not since I was about 15 and realised I had a problem with organising my homework diary at school, so created a new system that worked for me. I still don’t struggle with organisation much, despite being incredibly scatty some of the time. I’ve done a lot of work over the years on how to be effectively organised, and learnt a lot of workarounds. For example, I’ll often spend a few minutes at the start of a day working with my to-do list and boiling it down to three or four objectives for the day, which I will then write down on paper on my desk so that I can see it during the day and tick them off as I go. At some points in my life, I’ve created a fairly rigid timetable for myself, because that way I know I’ll get done what I need to get done.

But ask me to do a task when I don’t have a to-do list with me, or give me a piece of paper with information on that doesn’t have a file to go in, and you might as well not have bothered; I’ll have lost it or forgotten it before it gets anywhere near my diary planning.

John Allister

John Allister is the vicar of St Jude’s Church in Nottingham, England.

He is autistic, and has degrees in Theology and Experimental & Theoretical Physics.