Pillars of the church

This is part of a short series about some of the key features of Christian tradition and their relationship to neurodiversity.

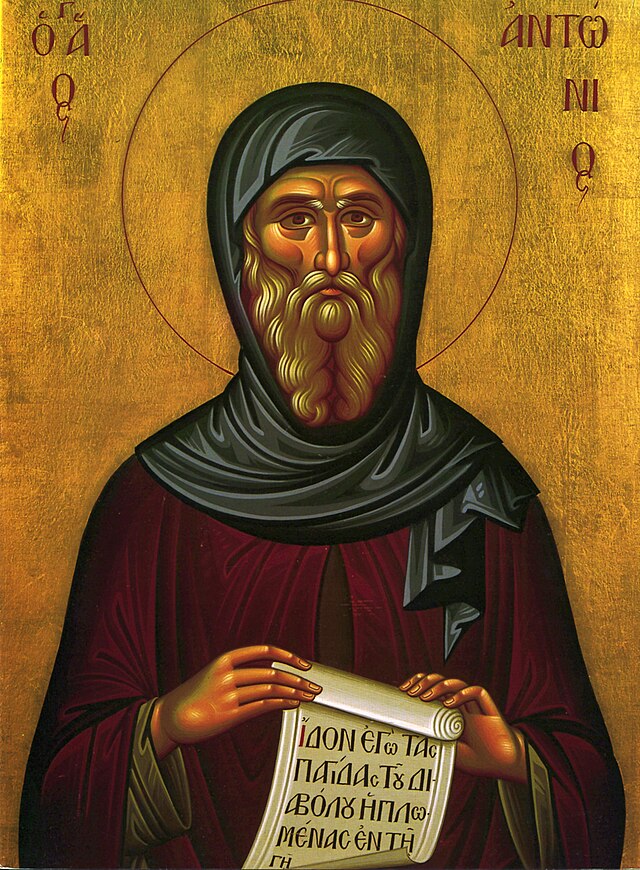

Saint Anthony the Great,

“Father of All Monks”

Further Reading

- Quiet in the Library!

- St Thomas Aquinas – patron saint of autism?

- Tips for Including Autistic Folk in Worship

- Practicing the Way (John Mark Comer)

Pillars of the church 1

Monks’ habits

Here are four elements of what it means to be a Christian. Each of them is really important; each of them has a place, and is a valuable correction against the others being misused. But none of them should be at the centre of faith, and if they start taking the centre spot then they can lead people away from God.

- Right habits and rituals

- Right doctrine

- Right experience of God

- Right actions in the world

Each of them also ends up being fairly central to a wing of the Church, and each of them has a different relationship to neurodivergence.

The emphasis on right habits and rituals first developed in the 300s AD. Within a generation, during the reign of the emperor Constantine (reigned AD 306-337), Christianity went from being a persecuted sect to being the official religion of the Roman Empire. All of a sudden, there were huge numbers of people or seeing faith as a means to social advancement and claiming to be Christians without it making much difference to their lives. The response of people like Anthony of Egypt (251-356) and Benedict of Nursia (480-547) was to retreat from the hubbub and wealth of urban life and adopt a deliberately different lifestyle, often with a written Rule of Life which required them to do things like reject material possessions and pray at regular times.

And that was doubtless valuable in their day. I can see why there is now a strong resurgence in it through people like John Mark Comer wanting Christians to be intentional about the influences that form them and deliberate in the habits we adopt in this world, especially when so many things in the world demand our attention.

There is real value in having a Rule of Life (though I greatly prefer the translation Pattern for Living). As an autistic person, it fits well with my strong preference for habits.

There are two main dangers that I see with it. The first comes from using someone else’s Rule. The people who devise a Rule may well decide on something that works for them with their neurotype and at their stage of life, but that doesn’t mean it works for me, or for an ADHD mum with a 6 month old baby who won’t sleep. There needs to be the flexibility for us to recognise what works for us. One example is the practice of silent prayer together. It’s never silent enough for me because of noise made by others, and someone with ADHD might well struggle to concentrate even if it was silent.

The other danger is that we start to measure our spiritual health by our rule-keeping. So “I haven’t managed to spend my 30 minutes in Bible reading and prayer today therefore I am a spiritual failure and God doesn’t love me.” Or even worse “I always keep to my rules, therefore I am a good person and God approves of everything I do.” That has been a danger for me too.

In some ways, this was what sparked the Reformation, of which more next time. But the key thing we need to remember is that relationship with God is central. The greatest command is to “love the Lord your God with all your heart, soul, mind and strength”, and the Bible says a lot about how God hates rituals when they exist for their own sake.

Having good habits of time with God are a really important part of following God, as long as they remain servants of our relationship with God rather than taking over the most important place.

John Allister

John Allister is the vicar of St Jude’s Church in Nottingham, England.

He is autistic, and has degrees in Theology and Experimental & Theoretical Physics.